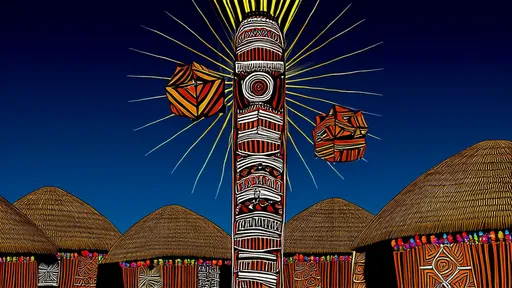

In the heart of Indonesian musical tradition lies the enchanting world of gamelan, an ensemble of percussive instruments that has captivated listeners for centuries. More than just a collection of gongs, metallophones, and drums, gamelan embodies a profound philosophical approach to sound, tuning, and harmony that reflects the cultural and spiritual values of the Javanese and Balinese peoples. The tuning systems of gamelan, known as laras, are not merely technical constructs but are deeply intertwined with cosmology, community, and a unique worldview that challenges Western notions of musical perfection. This article delves into the philosophical underpinnings of gamelan tuning, exploring how these ancient instruments create a sonic universe that is both mathematically intricate and spiritually resonant.

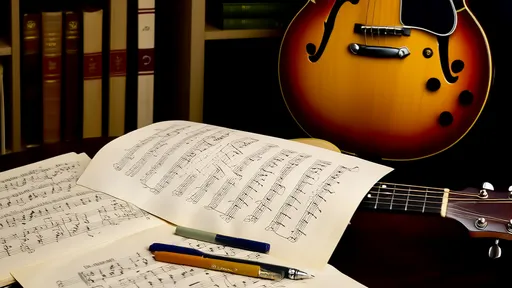

Gamelan ensembles are typically tuned to one of two primary systems: sléndro and pélog. Sléndro is a five-tone scale with nearly equidistant intervals, producing a bright, fluid sound that evokes a sense of openness and balance. Pélog, on the other hand, is a seven-tone scale with uneven intervals, often described as more expressive, emotional, and complex. However, these descriptions only scratch the surface. What makes gamelan tuning philosophically distinctive is that each set of instruments is uniquely crafted and tuned, meaning no two gamelan ensembles are exactly alike. This individuality is not seen as a flaw but as a virtue, emphasizing the importance of local identity and the acceptance of imperfection as a natural part of existence.

The philosophy behind gamelan tuning rejects the Western pursuit of standardized temperament, such as the equal temperament system used in pianos and other Western instruments. In equal temperament, intervals are slightly adjusted to allow for modulation between keys, creating a uniform but compromised tuning across all notes. Gamelan, by contrast, embraces a non-standardized approach where the intervals are based on natural acoustic principles and the preferences of the artisans who create the instruments. This results in a tuning that is "out of tune" by Western standards but is perfectly in tune with itself and its cultural context. The Javanese concept of rasa—a term that encompasses feeling, taste, and inner meaning—is central to this approach. The tuning is meant to evoke a specific rasa, connecting the listener to deeper emotional and spiritual realms.

Another key aspect of gamelan tuning philosophy is its connection to cosmology and harmony with the natural world. In Javanese culture, the universe is seen as a balanced system of opposing forces, similar to the concept of yin and yang. The two tuning systems, sléndro and pélog, are often interpreted as representing complementary dualities: male and female, light and dark, celestial and earthly. When performed together, they create a harmonious whole that mirrors the balance sought in life and nature. This cosmological alignment is not arbitrary; it is embedded in the very intervals of the scales, which are said to resonate with the frequencies of the cosmos. The act of tuning a gamelan is thus a spiritual practice, requiring not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of these broader philosophical principles.

Community and collaboration are also fundamental to the philosophy of gamelan tuning. Unlike Western orchestral instruments, which are designed to be played in any ensemble with standardized tuning, gamelan instruments are meant to be played together as a unified set. The tuning is specific to the group, and musicians must adapt to the unique characteristics of their ensemble. This fosters a sense of collective identity and interdependence, reflecting the communal values of Indonesian society. The process of creating and tuning a gamelan is often a communal effort, involving master artisans, musicians, and even spiritual advisors. The resulting music is not the product of individual virtuosity but of harmonious collaboration, where each instrument contributes to a greater whole.

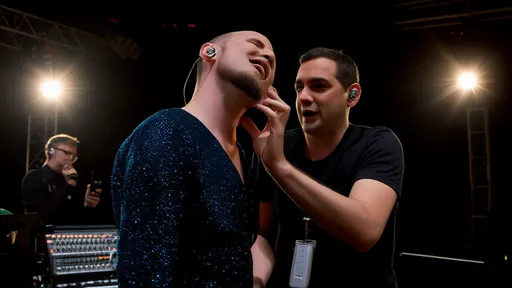

Moreover, the materials and craftsmanship involved in gamelan making are imbued with symbolic meaning. The bronze used for many gamelan instruments is considered a sacred material, associated with durability, purity, and spiritual power. The process of forging and tuning the instruments is ritualistic, often accompanied by ceremonies and prayers to ensure that the gamelan possesses a good "soul" or spirit. The tuner, known as empu, is revered not just as a technician but as a spiritual guide who listens intently to the instruments and adjusts them until they achieve the desired tonal quality and emotional effect. This holistic approach blurs the line between art, science, and spirituality, highlighting the deep integration of music into the fabric of life.

In contemporary times, the philosophy of gamelan tuning continues to influence modern music and thought. Ethnomusicologists and composers around the world have drawn inspiration from gamelan's unique approach to harmony and rhythm, incorporating its principles into new musical forms. The acceptance of "imperfect" tuning and the emphasis on collective sound over individual performance challenge modern Western ideals of precision and individualism. In an era where globalization often leads to cultural homogenization, gamelan stands as a testament to the value of local traditions and alternative ways of understanding sound and beauty.

In conclusion, the tuning philosophy of Indonesian gamelan is a rich tapestry of cultural, spiritual, and acoustic principles that offers a profound alternative to Western musical paradigms. Through its embrace of uniqueness, balance, and community, gamelan tuning encourages us to rethink our relationship with music and the world around us. It reminds us that harmony is not about conformity to a universal standard but about finding balance within a specific context, and that true beauty often lies in the imperfections that make each voice distinct. As we listen to the resonant tones of a gamelan ensemble, we are hearing not just music, but an ancient philosophy expressed through sound—a philosophy that continues to resonate across time and cultures.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025