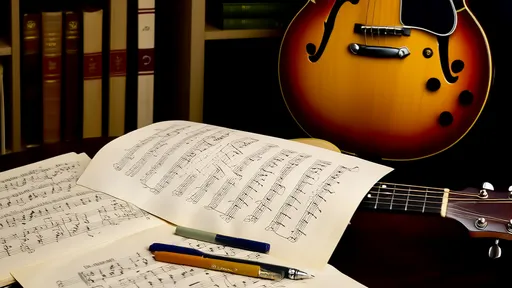

The Beatles didn't just change music—they rewired its DNA. While most discussions of their legacy focus on cultural impact or lyrical innovation, a quieter revolution was happening in the very architecture of their songs: the chord progressions. For decades, popular music had operated within a relatively safe harmonic playground, leaning on established patterns that felt familiar and comforting. Then came four lads from Liverpool who treated these conventions not as rules, but as suggestions.

What made The Beatles' approach to harmony so radical wasn't merely their use of unusual chords, but their fundamental reimagining of how chords could relate to one another. They demonstrated that emotional resonance didn't require complex jazz extensions or academic sophistication—it could emerge from bold, simple, yet profoundly unexpected moves. The deceptive cadence in And I Love Her, where a minor chord resolves not to the expected major tonic but to another unexpected major chord, creates a feeling of suspended, endless devotion. It's not just clever—it's emotionally precise.

Their innovation often stemmed from a combination of innocence and audacity. Largely self-taught, McCartney and Lennon were not constrained by formal music theory. They followed their ears, chasing sounds that felt interesting, fresh, or simply "right" for the song's narrative. This led to what theorists now call "modal mixture," freely borrowing chords from parallel major or minor scales. The famous Hard Day's Night opening chord—a chiming, ambiguous cluster that sparked decades of debate—is the ultimate example. It doesn't announce a key as much as it announces a new way of thinking: the journey is more important than the destination.

This exploratory spirit infused their entire catalog. In Ticket to Ride, the verse oscillates between A major and the stark, unexpected G major, creating a sense of weary travel and emotional distance that perfectly mirrors the lyrics. Michelle introduces a lush, romantic descent using an F7 chord (in the key of C) that feels both sophisticated and effortlessly natural. They weren't showing off; they were serving the song, using harmony as a color palette to paint specific feelings that words alone could not capture.

Perhaps their most significant contribution was democratizing musical complexity. They smuggled avant-garde ideas into the top of the pop charts, making millions of listeners subconsciously comfortable with dissonance, chromaticism, and abrupt key changes. The abrupt shift from the chorus of We Can Work It Out into a frantic, waltz-time middle section in a minor key shouldn't work in a pop song. Yet, it becomes a masterstroke, sonically illustrating the tension and resolution described in the lyrics. The Beatles made the unconventional feel inevitable.

Their later work with producer George Martin in the studio allowed them to transcend even the limitations of their instruments. A song like Because, with its haunting, layered vocals, is essentially a study in harmony, its beauty derived almost entirely from the movement between chords. It’s a clear line from these experiments to the intricate vocal harmonies of later bands like Queen or the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds, an album famously inspired by The Beatles' own rubber soul.

The enduring lesson of The Beatles' chord progressions is not a specific technical trick, but a philosophy: emotional truth trumps theoretical correctness. Their songs remain timeless because the harmony speaks directly to the heart. A diminished chord creates anxiety, a sudden major chord brings sunshine, a borrowed minor chord introduces a touch of melancholy. They understood the psychological weight of harmony and used it to craft miniature, three-minute worlds of profound depth and feeling. They taught us that a song could be both a catchy hit and a masterclass in composition, proving that the most powerful innovations are often those that feel, in hindsight, beautifully simple.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025