In the heart of Africa's musical traditions lies a complex rhythmic structure that has fascinated scholars and musicians alike for centuries. This intricate system, often referred to as polyrhythm or cross-rhythm, represents more than just musical expression—it embodies a sophisticated mathematical framework that has recently garnered attention from mathematicians and computer scientists worldwide. The African polyrhythmic model, with its interlocking patterns and temporal complexities, offers a unique window into how rhythm can be quantified, analyzed, and even applied to modern technological challenges.

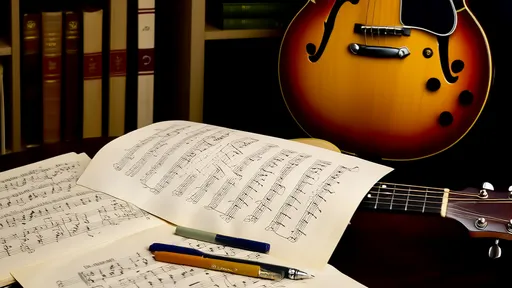

The foundation of African polyrhythm rests on the simultaneous use of multiple rhythmic patterns that, while independent, create a cohesive whole. Unlike Western musical traditions that often emphasize a single time signature, African rhythms frequently employ two or more conflicting meters played together. For instance, one musician might play in a pattern of three beats while another plays in four, resulting in a rhythm that repeats every twelve beats—the least common multiple of both patterns. This creates what is known as a timeline or key pattern, which serves as the structural backbone for many West African musical forms, particularly those from the Ewe, Yoruba, and Mandé cultures.

What makes these rhythms mathematically intriguing is their inherent combinatorial properties and cyclic nature. When deconstructed, they reveal complex relationships between prime numbers, least common multiples, and mathematical sequences. The rhythms often follow what mathematicians call "maximal evenness"—a distribution of beats that is as evenly spaced as possible within a given cycle. This property not only creates a satisfying auditory experience but also demonstrates an intuitive grasp of mathematical optimization that predates formal mathematical notation.

Recent research has begun formalizing these rhythmic patterns using mathematical models that draw from number theory, combinatorics, and group theory. Scholars have developed algorithms that can generate traditional African rhythms based on mathematical principles, confirming that these complex patterns follow precise mathematical rules despite their oral tradition. The study of these rhythms has led to the development of new mathematical concepts, such as the "rhythm necklace"—a circular representation of rhythmic cycles that illustrates their symmetric properties.

The applications of this mathematical model extend far beyond musicology. Computer scientists have found value in African rhythmic structures for developing new algorithms in scheduling and load balancing. The same principles that allow multiple rhythms to coexist without conflict can be applied to computer networks where multiple processes must share resources efficiently. Similarly, researchers in robotics have looked to polyrhythmic models for developing coordinated movements in multi-robot systems, where different robots must perform independent tasks that collectively achieve a common goal.

In the field of cognitive science, the African polyrhythmic model has provided insights into human perception and timing. The brain's ability to process multiple conflicting rhythms simultaneously demonstrates remarkable neural flexibility. Studies have shown that musicians trained in African polyrhythmic traditions develop enhanced cognitive abilities, particularly in temporal processing and multitasking. This has led to new approaches in music therapy, especially for neurological conditions that affect timing and coordination.

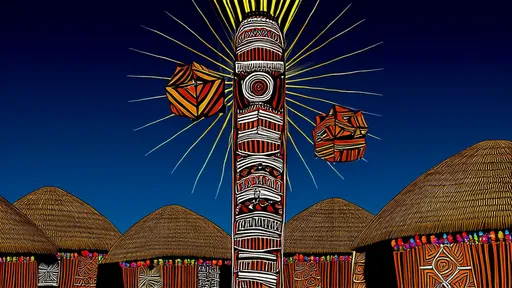

Perhaps most fascinating is how these mathematical principles manifest in other aspects of African culture beyond music. Similar patterns appear in textile designs, architectural layouts, and even social organizations. The same mathematical sensibility that structures rhythmic patterns can be found in the arrangement of villages, the organization of time in agricultural cycles, and the distribution of responsibilities within communities. This suggests a deep-rooted mathematical worldview that permeates multiple dimensions of cultural expression.

Despite its sophistication, the mathematical foundation of African rhythm remained largely unrecognized by Western scholars until recent decades. The oral transmission of these traditions meant that the underlying principles were rarely written down or formally analyzed. However, with growing interest in ethnomusicology and computational musicology, researchers are now documenting and formalizing these rhythmic systems with appropriate mathematical rigor. This work not only preserves important cultural heritage but also enriches the global mathematical community with alternative approaches to problem-solving.

The study of African polyrhythmic mathematics represents a beautiful convergence of art and science, intuition and formalism, tradition and innovation. As researchers continue to explore this rich territory, they uncover not just the mathematical genius embedded in cultural practices but also new tools for addressing contemporary challenges. From improving computer algorithms to understanding human cognition, the rhythmic mathematics of Africa continues to inspire and inform across disciplines.

What makes this field particularly exciting is its interdisciplinary nature. Mathematicians, musicians, anthropologists, and computer scientists are finding common ground in the study of these rhythmic structures. International collaborations between African cultural practitioners and Western researchers are helping to ensure that this knowledge is studied respectfully and accurately, with proper acknowledgment of its cultural origins. These partnerships are not only advancing academic knowledge but also fostering greater cultural appreciation and exchange.

As we move further into the digital age, the principles underlying African polyrhythm may find even broader applications. The complex synchronization required in distributed computing systems, the temporal patterns in data transmission, and even the design of user interfaces could benefit from these ancient yet advanced mathematical concepts. The fact that these models have been stress-tested through centuries of cultural practice gives them a robustness that newly invented systems often lack.

Ultimately, the African polyrhythmic model stands as a testament to human ingenuity—proof that sophisticated mathematical thinking exists outside formal educational systems and Western traditions. It reminds us that mathematics is not merely an abstract discipline but a living, breathing part of human culture that manifests in diverse forms across different societies. As we continue to explore this rich mathematical heritage, we not only expand our technical capabilities but also deepen our appreciation for the diversity of human intelligence.

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025

By /Aug 22, 2025